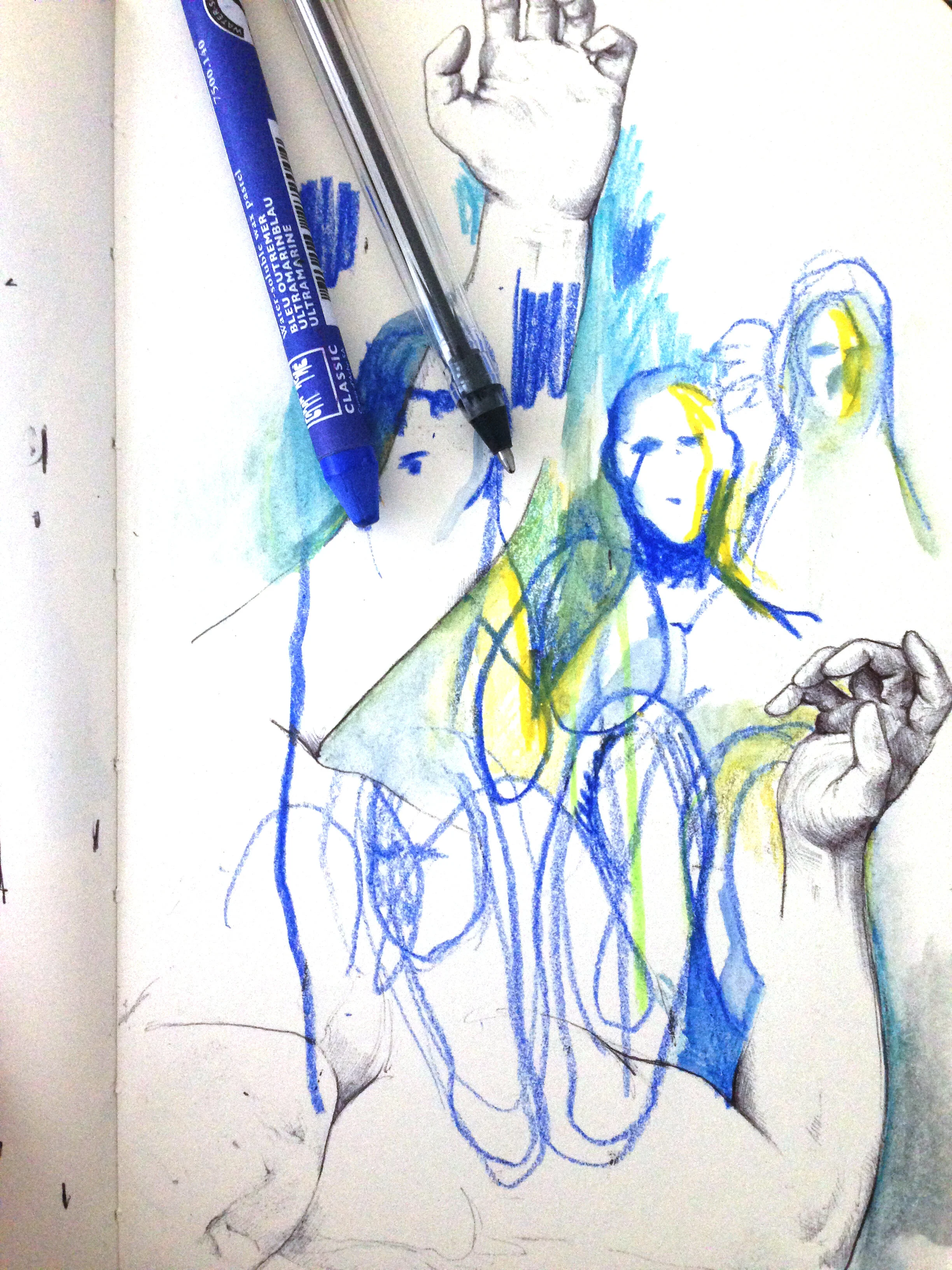

Blanda, Artist

Blanda is a Swiss contemporary artist living and working between New York and Los Angeles. In 2007, Blanda moved to New York to enroll in the School of Visual Arts (SVA) where she received the Silas H. Rhodes Scholarship.

Blanda is a Swiss contemporary artist living and working between New York and Los Angeles. In 2007, Blanda moved to New York to enroll in the School of Visual Arts (SVA) where she received the Silas H. Rhodes Scholarship. Her style, a mélange of collage, printmaking, drawing and painting, drew the attention of her professors, and after graduating in 2010 she was picked up by The New York Times for a coveted Art Director position.

Who are you?

Still trying to figure that one out myself…it’s way more of a transcendental search than I had anticipated a decade or so ago.

What did you want to be when you were a kid?

I always wanted to be a creative. But also a ninja. And maybe a scientific researcher and an Olympic swimmer.

What do you love?

Here is a small selection of things I love: Finding simple solutions to complicated things. The smell of coffee. Books. Boys with blue or green eyes. Large sweaters. Feeling sun on my skin. The color blue. Things that are hand made. Petrichor. This one beach in Greece. Waking up hungry. Forgetting time. Going to museums alone. The shape of hands.

Where do you find inspiration?

It usually finds me. That’s the whole thing with inspiration, it can’t be forced. It flows when it flows and sometimes it doesn’t. But exposing myself to creativity, and being part of a social environment that provides creative input obviously nurtures inspiration.

What’s your creative process like?

It varies from project to project. When I work on my own projects and art I try to be as close to myself as possible and minimize rational thought. When I work on a commercial project or a more graphic design based job I usually start in an intellectual place and do a ton of research. After I have absorbed enough information I throw it all out and start making stuff and see what happens. It’s usually quite interesting what comes out of subconscious memory.

What is something you had to learn the hard way?

Most things in our life are not within our control. I used to really make myself crazy over things I had no impact on whatsoever. Until I realized that I do have the power to change how I react to things that happen to me. Learning that has made me a lot more relaxed.

What is one thing most people would be surprised to learn about you?

My second major in art school was Physics (I was especially into Astro, Nuclear and Quantum Physics).

How do you define success?

Success for me is to be able to do what I love and feel entirely fulfilled and happy by that. Commercial success can be a desirable consequence of that but isn’t a necessity for me. Financial stability is a factor but only to cover my basic needs without having to stress out over it. Anything beyond that point is just one more cherry on top. That is not to say, that I don’t have high standards (I do!) but I will choose the life of a happy painter in the Provence over the one of a famous depressed artist any day of the week!

What’s the best advice you have for aspiring artists?

Accept and develop your style. Don’t try to change your natural hand, don’t paint like someone else but practice your very own individual style instead. Being inspired by other artists is obviously part of it but learn how to love your individual and intuitive creative expression. This has a lot to do with self-acceptance by the way. Possibly the hardest and most important lesson to learn.

How would you describe your art to someone who couldn’t see?

Well, that’s tricky because I would have to refrain from any visual reference. I would say that I paint and draw what I feel and that I want that feeling to transcend and translate into my work and from there to the viewer. I want it to be the equivalent to a really beautiful song or written passage. Something that evokes melancholy and longing in the most beautiful way possible.

How do you think we can make the world a better place?

By becoming more connected. To ourselves and to each other. We are in the midst of some kind of digital apocalypse, a rational and intellect-based crisis that demands an analogue counter movement. Not to go too esoteric on you here but we need to learn to put kindness first and not competition, to be compassionate and humanistic and recognize that separation is an illusion.

Blanda has worked with: OBEY, Kiehl’s, Volvo and DC Shoes, Elena Ghisellini, TopShop and Barbara Bui have commissioned Blanda for art-driven collaborations. Her work has been featured in media outlets such as Vogue, New York Magazine, Vice, WWD, Glamour Magazine, Elle and Rolling Stone have covered her work.

Find more Blanda:

Website: www.blandablanda.com

Instagram: @blahblahblanda

Manufacturing Fear: How Data Became the Most Powerful Political Weapon

I come to this conversation from direct experience. I spent years working in marketing and advertising, specializing in social campaigns and audience behavior, eventually becoming one of the top consultants in this space across several industries…

I come to this conversation from direct experience. I spent years working in marketing and advertising, specializing in social campaigns and audience behavior, eventually becoming one of the top consultants in this space across several industries, and developed a deep fluency in how audience data, psychology, and targeted messaging can influence behavior and drive purchasing decisions… But over time, the work began to feel increasingly hollow, often pushing people toward things they didn’t need or creating desires that weren’t truly their own. Filmmaking had always been my real goal, so I eventually left brand work behind, using the skills I’d developed to transition into the entertainment industry and apply that same understanding of audiences toward something more meaningful, connecting people with stories rather than persuading them to buy something. Now working as a filmmaker, I’m grateful to be far removed from that world, though my time inside it revealed how powerful these tools can become in the wrong hands.

At our core, people are fairly simple. We gravitate toward our interests, our hobbies, and the communities that feel authentic to us. Marketing has always tapped into those affinities; that part isn’t new. What is new is the scale and precision made possible by social media platforms and data extraction. Companies led by figures like Mark Zuckerberg, Peter Thiel, and Elon Musk now operate with unprecedented access to personal behavioral data, shaping information flows and social dynamics in ways that often deepen division rather than strengthen communities. Many critics argue that powerful actors have exploited these systems for profit and influence, contributing to social fragmentation and mistrust, especially amid ongoing controversies and revelations surrounding elite networks and abuses of power. Whether through negligence, indifference, or active pursuit of profit above all else, the result feels the same: communities pulled apart while enormous wealth concentrates at the top. Below is a deeper look at the real harms created through the exploitation of our data.

THE PROBLEM

The exploitation of our data affinities and personal interests by powerful tech elites is one of the most dangerous developments of the modern digital age. When companies like Meta and Palantir construct empires built on the extraction and manipulation of human behavior - while billionaires increasingly consolidate influence through the ownership of major media institutions like The Washington Post and Paramount—the harm extends far beyond privacy violations; it strikes at the foundations of autonomy, democracy, and truth itself.

At the most basic level, our data affinities are intimate reflections of who we are: what we fear, what we desire, what we believe, and what we might become. When these signals are harvested at massive scale, corporations gain the ability not only to predict behavior, but to shape it. Platforms no longer simply reflect our preferences; they actively steer them, optimizing for engagement, profit, and power rather than well-being or social good. Human attention becomes a commodity, and people become instruments within systems designed to keep them reactive, predictable, and profitable.

The political danger emerges when this behavioral power is used to manipulate public emotion, particularly fear. Data-driven platforms learn precisely which messages provoke anxiety, outrage, tribal loyalty, or resentment… and then amplify them. Fear spreads faster than nuance. Anger generates more engagement than reason. Algorithms reward the most emotionally activating content, regardless of accuracy or social consequence.

The result is a public sphere increasingly shaped by manipulation rather than deliberation. Citizens are pushed toward emotional reaction instead of reflection. Complex issues are reduced to outrage cycles. Political actors, both domestic and foreign, can exploit these systems to divide populations, suppress trust in institutions, and mobilize people around perceived threats rather than shared solutions. Democracy depends on citizens capable of independent thought and informed debate, yet these systems bypass reason and trigger reflex.

The danger intensifies when this influence is concentrated in the hands of a few unaccountable actors. Companies wielding data resources and algorithmic power rival nation-states in influence, yet operate without democratic oversight. Their platforms increasingly determine which information spreads, which narratives gain legitimacy, and which voices are amplified or buried. Shared reality fractures into personalized information bubbles, making consensus nearly impossible.

Even more troubling is how these systems exploit psychological vulnerabilities at scale. Platforms learn what makes individuals feel insecure, validated, or afraid, then feed them more of it to maintain engagement. Fear and identity-based conflict become business assets. Polarization deepens, radicalization accelerates, and populations become easier to manipulate politically and economically.

There is also a chilling effect on freedom itself. When people know their behaviors and beliefs are constantly monitored, they self-censor. Exploration narrows. Political dissent becomes riskier. Innovation and democratic participation decline as conformity becomes safer than questioning. Surveillance doesn’t need to be overt; its mere presence reshapes behavior.

Children and young people are especially vulnerable. Their psychological development now unfolds within systems designed to capture attention and shape behavior before they can meaningfully consent. Emotional manipulation becomes normalized from an early age, embedding patterns of dependency and comparison that persist into adulthood.

Geopolitically, data concentration creates new forms of power. Detailed psychological and demographic profiling enables targeted propaganda and information warfare across borders. Elections and social movements become vulnerable to invisible influence campaigns designed to inflame division and undermine trust.

Security risks add another layer: massive data stores inevitably attract breaches, exposing intimate details of millions of lives. Personal histories cannot be reset once stolen, creating long-term vulnerability.

Culturally, personalization fragments shared experience. Citizens increasingly inhabit separate informational realities. Without common reference points, public dialogue collapses into conflict, and compromise becomes impossible.

At the moral core lies a deeper problem: human emotion itself becomes raw material for profit. Loneliness, fear, hope, curiosity… every signal is captured and monetized. Emotional states become inputs in business models that reward systems capable of keeping people anxious, reactive, and engaged.

The next wave of artificial intelligence threatens to magnify these risks. As predictive systems grow more sophisticated, platforms will anticipate needs and influence decisions before individuals consciously recognize them. Persuasion becomes personalized, invisible, and continuous. Machines may understand human behavior better than humans understand the systems shaping them.

Ultimately, the exploitation of data affinities is dangerous because it shifts power away from individuals and communities and toward opaque systems optimized for control rather than dignity. Freedom becomes something performed rather than lived. Choice persists in form but not always in substance.

The deepest fear is political: that societies governed by citizens making independent decisions will slowly transform into populations guided by engineered emotion, especially fear… shaped by systems designed to influence rather than inform.

If left unchecked, this trajectory risks creating a world where algorithmic incentives outweigh human values, where shared reality dissolves, and where those with the most data know us better than we know ourselves, allowing bad actors to exploit these systems and use that knowledge not to empower us, but to manipulate us and pull communities apart.

THE RESPONSE

A meaningful response starts with recognizing that this problem isn’t abstract—it affects how we think, how we relate to each other, and how our societies function. So the call to action has to be both personal and collective.

First, we have to reclaim agency over our own attention. That means being conscious of how platforms try to provoke emotional reactions… especially fear and outrage, and refusing to let algorithms decide what we care about. Slowing down before sharing, questioning emotionally charged content, and seeking out diverse sources of information are small acts, but they restore independence of thought.

Second, we must demand transparency and accountability from the companies and legislators who shape our information ecosystems. Supporting stronger data privacy laws, algorithmic transparency, and regulation of behavioral targeting isn’t anti-technology, it’s pro-democracy. The digital world has grown faster than the rules governing it, and citizens must push policymakers to catch up.

Accountability must extend to the companies and leaders who have amassed unprecedented influence over how information moves through society. Companies like Meta, X, Google and Palantir wield enormous power through platforms and technologies that shape public discourse, behavior, and access to information. Holding these companies accountable means demanding meaningful limits on how personal data is collected and used, increasing transparency around algorithmic systems, and reducing the unchecked access corporations have to our lives and attention. Rebalancing that relationship is not about rejecting technology, but about ensuring it serves the public interest rather than undermines it.

The goal isn’t to reject technology or retreat from the digital world, because I believe we can find real community and build meaningful connections there. It’s to ensure that human dignity, truth, and community come before profit, engagement metrics, and systems that divide our communities. The future of public discourse, democracy, and even personal autonomy depends on whether we choose to take that responsibility seriously now, rather than later.

Fourth, we need to rebuild real-world community. Algorithmic systems thrive when people are isolated and angry. Shared physical spaces, local organizations, arts communities, schools, neighborhood initiatives, and cultural events… create bonds that can’t be easily manipulated by digital systems. Strong communities are harder to divide.

Fifth, those of us who work in media, storytelling, technology, and culture have a responsibility to use our skills ethically. Stories, films, journalism, and art can reconnect people rather than divide them. Technology itself isn’t the enemy -- its purpose and governance are what matter.

The goal isn’t to reject technology or retreat from the digital world, because I believe we can find real community and build meaningful connections there. It’s to ensure that human dignity, truth, and community come before profit, engagement metrics, and systems that divide our communities. The future of public discourse, democracy, and even personal autonomy depends on whether we choose to take that responsibility seriously now, rather than later.

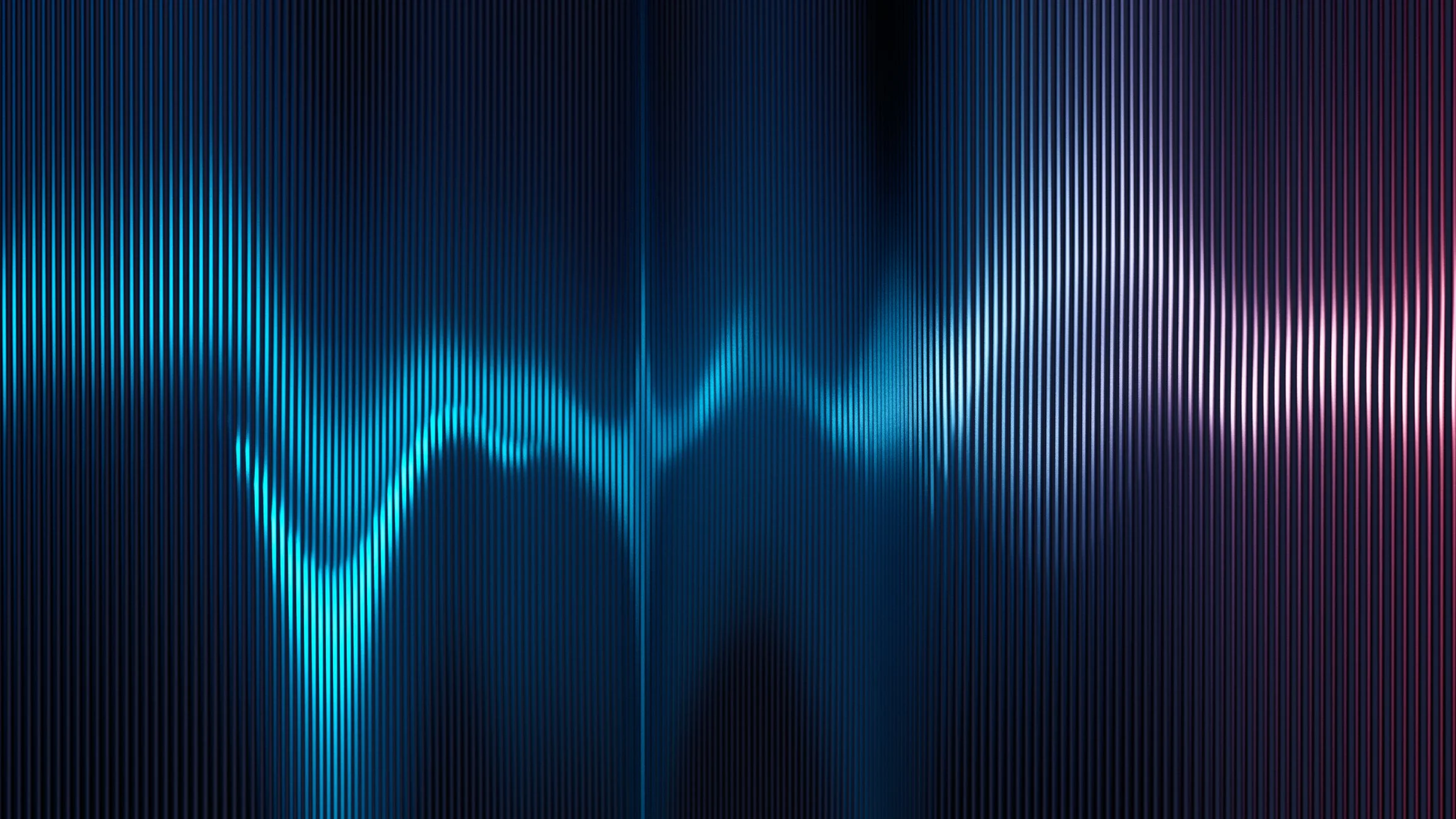

Metric - Risk, Official Music Video

It was an honor to direct the latest Metric music video for Risk. Last summer, I had the pleasure of working with the band on a documentary series, and in that time I came to appreciate just how intentional and thoughtful their creative…

It was an honor to direct the latest Metric music video for Risk. Last summer, I had the pleasure of working with the band on a documentary series, and in that time I came to appreciate just how intentional and thoughtful their creative process is, especially Emily’s songwriting, which carries both emotional precision and a fearless honesty.

When I asked about the song, Emily described Risk as addressing the dizzying speed at which connections are formed and discarded today, where emotional survival can feel dependent on dexterous texting, and our ability to communicate often falters outside our devices. She speaks to the way self-sabotage, defensiveness, and cynicism can end things before they truly begin, trapping us in cycles we barely recognize. And yet, there’s hope in the idea that another path exists, another way forward, if we’re willing to take the chance.

Inspired by those words, I wanted the video to live inside that emotional space, suspended somewhere between intimacy and distance, clarity and disorientation. I wanted to lean into the interplay of space, time, and light to reflect the tension between connection and isolation, allowing performance and atmosphere to guide the visual language.

Part of that exploration of disorientation came through the way we approached the image itself. So much of how we experience the digital world now is compressed into sharp, fast, disposable fragments, everything optimized for speed, clarity, instant consumption. But that’s not how memory works, and it’s not how emotion feels. Our real experiences blur at the edges. Moments drift in and out of focus. Sometimes clarity arrives late, and sometimes it never fully arrives at all.

I wanted the video to allow for that softness, moments where the image slips slightly out of focus, where light blooms and movement feels suspended. Not as a stylistic trick, but as something closer to how we actually see and remember, imperfect, emotional, fleeting. The softness creates space for reflection, vulnerability, and uncertainty, the very feelings the song wrestles with.

In resisting the impulse to make every image hyper sharp or cut every moment short, we embraced a fluid but ambitious approach, using a continuous oner to help tie the narrative together. This allowed us to give the audience room to breathe inside the performance, to sit with Emily in those in between states where connection feels fragile but still possible. The idea takes shape through a visual journey in which she moves through different environments, some vast and open, others compressed and intimate, mirroring the emotional shifts within the song itself.

The hope was to create something that felt both honest and dreamlike, a visual expression of the vulnerability and courage it takes to risk connection in a world that often makes it feel easier not to.

Producer: Kristina Fleischer

Producer: Rebecca Parks Fernandez

Director: Duane Hansen Fernandez

Director of Photography: Alice Gu

Assistant Camera Op: Chris Jones

Steadicam Operator: Travis Montgomery

Hair & Make Up: Gina Ribisi

Editor: Hugh Westhoff

2nd AC/DIT: Nick Strauser

Gaffer: Scott Spencer

Grip: David Gonzalez

Best Boy: David Albarran

The Smith Society Podcast — Conversations About Storytelling

The Smith Society is a podcast that focuses on the intricacies of storytelling, while giving an open and honest platform for each guest to shine and provide their own insight to empower each listener through the…

When I started The Smith Society Podcast, the idea was simple: create a space where storytellers could talk honestly about their work, their journeys, and the unpredictable paths that lead to creating something meaningful.

So many of the best conversations in film happen off-camera; after screenings, between setups, on late-night drives home, or sitting around with collaborators trying to figure out how to make the next project happen. I realized those were the conversations people rarely get to hear. The podcast grew out of wanting to share that space.

At its core, The Smith Society is about storytelling and the people who dedicate their lives to it. Each episode brings together actors, writers, directors, producers, and creatives across film and television to talk about craft, career paths, creative struggles, breakthroughs, and the realities of working in an industry that constantly evolves. I try to keep the conversations grounded and personal. The goal isn’t promotion… it’s understanding the person behind the work. Because audiences don’t just love finished films or shows, they’re curious about how those stories came to be.

The Smith Society podcast on Spotify & Apple. Or, you can find us wherever you listen to podcasts.

Conversations That Capture the Spirit of the Show - Every guest brings a different perspective, but a few episodes really capture what the show aims to do.

Lee Sung Jin — Trusting Personal Stories

My conversation with Lee Sung Jin, creator of BEEF, explored how deeply personal experiences can shape globally resonant storytelling. We talked about risk, authenticity, and trusting instinct over formula.

There’s always pressure in the industry to follow trends. Lee’s work is a reminder that the stories that truly connect are often the most personal ones.

Amir El-Masry — Persistence and Identity

One of our earliest episodes with Amir El-Masry set the tone for the series. Amir spoke openly about navigating identity, career uncertainty, and the patience required to build a meaningful acting career.

What stood out was how universal creative struggle is. No matter the discipline, persistence and belief in your voice matter.

Justin Chon — Passion vs. Practicality

Justin Chon shared insights from making films like Blue Bayou, balancing passion projects with the realities of filmmaking as a business. His perspective resonated with anyone working independently, the constant negotiation between creative ambition and practical limitations.

It’s a conversation about making films that matter while still figuring out how to survive long enough to make the next one.

Gabriela Cowperthwaite — Documentary as Urgency

Talking with Gabriela Cowperthwaite expanded the conversation into documentary storytelling and filmmaking as investigation. Her work shows how film can operate not just as entertainment, but as social reflection and inquiry.

It reminded me how powerful storytelling becomes when it engages with real-world stakes.

Why Physical Media Still Matters

One episode that felt especially personal was my reflection on physical media; DVDs, Blu-rays, records — and why they still matter. Growing up collecting films and music, I’ve always believed stories should be preserved and revisited.

In an era where movies quietly disappear from streaming platforms, owning a story feels increasingly important. That conversation became less about nostalgia and more about memory, access, and preservation.

Why I Keep Making the Show

What keeps me excited about the podcast is the reminder that no two creative journeys look the same, yet we’re all chasing similar things… connection, meaning, and the hope that our work resonates with someone else.

Every conversation reinforces that storytelling is ultimately about people. About collaboration. About learning from one another. And honestly, I still feel like I learn something new every time we record.

Looking Ahead

Moving forward, my hope is to keep expanding the range of voices on the show — not just filmmakers, but artists and creators across disciplines who think deeply about storytelling and culture.

If you love movies, storytelling, or simply want to understand how creative work actually gets made, I hope you’ll check out the podcast.

Because stories don’t exist in isolation. They’re shaped by people, experiences, and conversations — and this podcast is my way of keeping those conversations going.

Left Field Project

With a series of interviews, Left Field Project captures what drives the world’s most progressive designers, artists and creators. Left Field Project began as an inside look into the mechanics of…

With a series of interviews, Left Field Project captures what drives the world’s most progressive designers, artists and creators. Left Field Project began as an inside look into the mechanics of inspiration, searching for what drives an individual to create. The end result was something far more fascinating.

Never before have so many outwardly driven and diversely talented individuals been slammed into one collaboration. Left Field Project is a beautifully-designed guide to get you from where you are to where you want to be. No matter your background, there is a path that can take you to your end goal, the trick is knowing how to find it.

Left Field Project features over 750 interviews.

John August, Screenwriter and Director

What’s most impressive about John August is not his incredible body of work (although it is impressive), it’s his willingness to share his knowledge with anyone who seeks it.

What’s most impressive about John August is not his incredible body of work (although it is impressive), it’s his willingness to share his knowledge with anyone who seeks it.

In a world where people don’t often offer helping hands to those in their shared field, August is a bastion of kindness and a seemingly bottomless pit of insight and wisdom into filmmaking. His wildly successful podcast, Scriptnotes, which is co-hosted by Craig Mazin, is a weekly mini-course into the behind-the-scenes process of entertainment. And sometimes grammar.

At the risk of discussing his actual writing credits last, his work on the technological side of screenwriting has changed not only the way writers share their work, but also the way they create it.

And, I guess lastly, he has written many great movies, television shows and a Broadway play. He’s been nominated for awards many times over.

John August is, to put it mildly, a jack of all trades.

What did you want to be when you were a kid? Did you always want to be a screenwriter?

I wanted to be a writer. I didn’t really understand that screenwriting was a thing. I knew that there were movies, I knew there were plays, but I didn’t ever make the leap that movies were written the way the plays were written.

It wasn’t until I watched War of the Roses — Danny DeVito’s The War of the Roses — and I went back and rewound the tape and started writing down everything in it and realized like, everything here was written. It sounds really naive now, but this was before the Internet. There wasn’t the sort of popular coverage of how movies got made. I realized there must be like a play behind this, a little light bulb went off and I started looking for examples of that.

The first screenplay I was able to read was Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies and Videotape. I read that and loved it, and saw that, wow… It’s actually what the movie is like before it’s a movie, and figured out I wanted to learn how to do that.

What do you love?

I love when someone does something unexpectedly amazing. A lot of times you can be very, very jaded. I love when something surprises me in a good way, where I thought I knew where something was going and then it surprises me and exceeds my expectations.

I think a lot of writing and a lot of creating art is how to handle the expectations of who is going to be viewing what you’re making. Everyone is going to approach whatever you’re trying to do with set expectations about the genre, about who you are as an artist, about what they think this work is supposed to be. A lot of your job is to anticipate those expectations, meet them most of the time and then exceed them in ways you didn’t expect. I love when I see something that blows me away because it wasn’t even doing what I thought it would do.

Do you think there is a specific genre that you see that more? Do you see it in plays or television?

This may be the golden age of television, and I think 10 or 20 years from now we will look back and say, “Wow, that was really an amazing time when things suddenly changed in remarkable ways.” We have shows as complicated as Game of Thrones doing so well, and things as honest and simple as New Girl or Girls dealing with sort of the everyday issues of people you don’t usually see on TV.

I think you see expectation-busting happening in television a lot. There are movies that certainly do that, and I think we still have our indies that do that. We have occasional big movies that break out that way, but the innovation seems to be happening on television or the newer television/web formats.

What’s your process like? How do you make creative happen?

I think creative happens because you continually ask questions and challenge the assumptions about how things are supposed to be. The last few years I’ve been making a lot of apps for Mac and for iOS, and where I think I’ve succeeded in doing that has been in looking at sort of what the status quo was in the industry and saying, “Well, why does it have to be that way? And why can’t I actually make a better version of that or why can’t I solve that problem?”

One of the first apps I made was called Bronson Watermarker which was literally just because I need to watermark these 45 scripts with different names on it and there was no good tool for me to do that, so I said, “Well, someone needs to start that tool and that should be me.”

I got frustrated looking at 12 pt Courier and I wanted a better 12 pt Courier, so I worked with a talented font designer, Alan Dague-Greene, to make a better Courier, and called it Courier Prime. I think it’s recognizing that the current situation can change, and using those that are available to make that change happen.

What is something you had to learn the hard way?

Everything takes much longer than you think it will take. There have been so many projects that I’ve started out at a sprint, and then eight months later I’m still in the service log. I’ve had to come to accept that things will never happen as quickly as you would like to see them happen. You need to anticipate that from the outset and make sure you’re not basing all your self esteem around the success of one project that may be years off in the horizon or may never happen.

The amount of work you do outside of screenwriting, with things like your podcast, it’s clear you want to help people in this industry. I can’t imagine you have a lot of free time, so why is it so important to you to help others?

I think that’s something you can say about artists in general, that they want to bend the universe a little bit in their direction and the direction they liked to go. In helping people on the podcast or the website, I just wish the state of screenwriting was a little bit better. I wish the state of writing was a little bit better. If I can do something to help nudge it in that direction, I will do that.

I’m also tremendously grateful for everything that other people have done before me and simultaneously with me without knowing I needed their help. When I need to do research and find out about cowboy hats of the 1870s, someone has a whole website about cowboy hats in the 1870s. If they are willing to be that resource for me, I should be that resource for somebody else. If everybody took the time to really document what they knew, the world would improve measurably.

If you could go back in time, say ten years, and give yourself some advice, what would that advice be?

I would probably pick projects more based on the collaborators and less on how much they excited me. One of the things I’ve recognized over the last decade is that it can be the best idea in the world for a movie but if you don’t believe that those are the people who can carry that movie across the finish line, you’re kind of spinning your wheels. Sometimes I’ve been attracted to the bright and shiny objects… I have written other people’s movies that they weren’t able to make. I should have spent more time writing the movies that I could make.

Who are some of your influences?

As a writer and as a filmmaker, I mean certainly James Cameron’s ability to marry his storytelling with his technical prowess is remarkable and it’s that nothing-can-stop-him quality that’s inspirational. I’m a frequent adviser to the Sundance Filmmakers Lab, and every year there’s a batch of new filmmakers who inspire me by their singularity of vision. They’re not trying to make somebody else’s movie, they’re trying to make their movie and that’s a good reminder because so often my function is to be the craftsman who’s there to help make this product better, and not necessarily more unique.

What is one thing people would be surprised to learn about you?

I’m a pretty good baker. I really like the sort of the weird, artisanal magic baking involves and then you don’t necessarily know how stuff is going to turn out until you spent two hours trying to make it. You can have some anticipation about how these flavors should combine, but you don’t know if the cake is going to rise, or if the cake is going to fall. I don’t bake as much as I would like to, but it’s actually one of the things I enjoy doing when I get the chance.

How do you define success?

I think you define success at being able to do what you want, when you want, and make enough of a living at it that you’re not kicking yourself. I think too often people define success based on other people’s opinions of them, and the problem with that is ultimately when you put your self esteem in someone else’s hands you risk your self-esteem being destroyed. It’s the same reason why I don’t read reviews anymore. Reviews can be a meaningful part of the cultural discussion, but I think reviews can also can be very destructive to the actual person who created the work. For that reason, I don’t read reviews of my own stuff anymore.

What makes a good script?

I’ll sit back and talk about what makes a movie a movie. Because most of what I work on are movies. Movies are a strange thing in that they’re a story that should only be able to happen once. It’s a unique set of circumstances with this character and this world and this incident that it begins a story that can only happen one way, with this character, in the situation. A good script has an interesting character facing interesting and seemingly insurmountable problems that through their own efforts they’re able to solve. That’s a very, very generic sort of baseline description, though. I think a lot of movies that don’t work don’t meet that test. Movies are never really about the plot. Movies are about those characters you are fascinated by, creating a plot in front of you.

How was the transition from writing to directing?

The luxury a writer has is I can sit in front of my computer and just take as long as I need to get it right, and I have absolutely 100 percent control over those words on the page, and those words are exactly the words I want them to be. Directing is honestly a process of surrendering some control, because ultimately you cannot make the actors be exactly the puppets you would like them to be. You can’t control every bit of light. You can’t control every bit of costume. Directing is ultimately a collaborative process. You have to be the leader of the team but you still have to rely on the team.

Part of the process of learning how to become a director is learning how to trust the people you’ve brought on to your team. How to talk to them in ways that stimulate them to be doing their best work without limiting them to your small vision. I know a fair amount about lighting, but I wouldn’t know how to light that scene as well as a qualified DP would. I know a lot about music, but I cannot create music the way a great composer can create music. It’s been a process of learning how to surrender some control.

What’s the best advice you have for someone just out of college?

I would say embrace what makes you unique and embrace your vision. If you don’t know what your vision is, spend some time figuring out what you love and what movie you would more than anything in the world want to see, and figure out how to make some version of that movie.

I think too often you become obsessed with trying to create something for somebody else, something they will like, and not focusing enough on creating the thing that is uniquely you that you could put out there into the world.

I think my process of getting more comfortable with speaking in front of crowds. My online persona has been just sort of learning to embrace the things that are weird about myself and take them as strengths rather than weaknesses.

What personality trait do you think is most important to a screen writer?

Perseverance and screenwriting is kind of a marathon activity. Anyone can sprint and get through small bits of writing, but a screenplay is a pretty big document. It’s 120 pages. You keep going back through it and revise it again and again and again and again. The ability to look at something for the 15th time and yet also look at it like it’s the first time is a uniquely difficult thing for screenwriters.

I think the novelist may pass through her words a couple times along the way, but a screenwriter is going back again and again, and it has to be able to be both the writer who’s in control of the scene and the audience who has no idea what’s happening next. Being able to shift back and forth between those perspectives is a tough skill to learn.

How do you think we can make Hollywood a better place?

I think Hollywood will always be broken and that’s because we’re trying to do a really difficult and impossible thing, which is make movies that are specific and interesting and terrific and yet will appeal to everyone on the planet. Those are not necessarily compatible goals. I would venture beyond Hollywood to say, how can we make cinema better, and I think that’s by being honest about the kind of movies we want to make, honest about the kind of movies we want to see. Supporting unique and individual voices and not settling.

I think right now television has risen and become a much more interesting place than our movies are. I think Hollywood — and filmmakers overall — can learn a lot of lessons from what’s going so well in television and make better movies.

How do you think we can make the world a better place?

It starts with taking personal responsibility for the things you can control. I think before you can fix other people’s situations, you have to make sure your own situations are fixed. The small things you can do in terms of not ruining the planet are the things you should do. Once those are in control, you can tackle the bigger issues.

You need to look at what citizenship means. Citizenship, we often think, means we have a civic duty for voting and being patriotic. Citizenship is really just recognizing that you are one of a group, locally and state-wise and nationally and globally, and recognizing there are difficult choices we make at every level. Make sure the people who you’re putting in power to make those decisions are the right people, and try to understand things that are beyond your own limited scope.

John August: www.johnaugust.com

John August Twitter: www.twitter.com/johnaugust

John August Instagram: instagram.com/johnaugust

John August IMDb: www.imdb.com/name/johnaugust

WRITER EMERGENCY PACK

Helping writers get unstuck

John August’s kickstarter campaign: Writer Emergency Pack is a deck full of useful ideas to help get your story back on track. Writing is hard. You’re constantly trying to figure out what word comes next.

Creative writing is even harder. When you’re working on a story, you’re not just trying to decide what word comes next, but what idea comes next.

It’s easy to get stuck.

I know what that’s like because I’m a screenwriter. I’m lucky to have had ten movies produced, from GO to BIG FISH to FRANKENWEENIE. I also host a popular podcast about film and television called Scriptnotes.

Over the years, I’ve had conversations with hundreds of writers, both on the podcast and around the lunch table. No matter what genre or medium, all writers face story problems. Plots that plod. Characters that don’t connect.

Every writer has her own techniques for pushing past these problems — little nudges and prompts to help get the story clicking.

Writer Emergency Pack is a curated collection of some of the most useful suggestions I’ve encountered. It’s by writers, for writers.

Learn more about Writer Emergency Pack: http://kck.st/1obEMOQ

SCRIPTNOTES PODCAST

Each week, screenwriters John August and Craig Mazin discuss screenwriting and things that are interesting to screenwriters, everything from the craft to the business to the best ways to actually get yourself writing.

www.johnaugust.com/scriptnotes

Highland [App]: quoteunquoteapps.com/highland *The better way to write a screenplay.

Bronson Watermarker [App]: quoteunquoteapps.com/bronson

Weekend Read [App]: itunes.apple.com/us/app/weekend-read

Writer Emergency: www.writeremergency.com

Courier Prime: www.johnaugust.com/2013/introducing-courier-prime

Special thanks to Stuart Friedel for orchestrating everything.

Alex Bogusky Interview

Alex Bogusky began his career over 20 years ago when he joined Crispin and Porter Advertising in 1989 as an art director. Alex became the creative director five years later, a partner in 1997, and co-chairman in 2008. Under Alex’s direction, Crispin Porter + Bogusky grew to more than 1,000 employees, with offices in Miami, Boulder, Los Angeles, London and Sweden, and with annual billings over $1Billion.

Alex Bogusky began his career over 20 years ago when he joined Crispin and Porter Advertising in 1989 as an art director. Alex became the creative director five years later, a partner in 1997, and co-chairman in 2008. Under Alex’s direction, Crispin Porter + Bogusky grew to more than 1,000 employees, with offices in Miami, Boulder, Los Angeles, London and Sweden, and with annual billings over $1Billion. During Alex’s leadership, CP+B became the world’s most awarded advertising agency. CP+B is the only agency to have won the Cannes Advertising Grand Prix in all five categories: Promo, Media, Cyber, Titanium, and Film. In 2008, Alex was inducted into the Art Director’s Club Hall of Fame. In 2010, Alex received the rare honor of being named “Creative Director of the Decade” by Adweek magazine.

Alex has always been drawn to social responsibility. While at CP+B, Alex created groundbreaking cause initiatives like the “Truth Campaign,” the most successful youth-focused, anti-tobacco education initiative in US history. He also helped Al Gore debunk the notion of “Clean Coal,” with TV spots directed by the Coen Brothers of “Fargo” fame.

With FearLessRevolution.com he has continued his work on Climate with Al Gore, rebranding Gore’s Climate Reality Project and launching 24 Hours of Reality last year – the highest-viewed streaming web event to date with 8 million viewers tuning in for an average of 58 minutes. With FearLess he also launched COMMON, the world’s first collaborative brand. COMMON is a creative community for rapidly prototyping social ventures, all done under the world’s first collaborative brand. Most recently, he helped launch MadeMovement, a new marketing agency in Boulder, Colorado, dedicated to the resurgence of American Manufacturing.

I’m incredibly inspired by the evolution of Alex’s career and life- the way he has moved from advertiser to advocate- seeing a need for a higher sense of social responsibility and acting on it.

What did you want to be when you were a kid?

A lot of different things. Like a lot of kids, I remember I wanted to be a jet fighter pilot. I was really into World War II airplanes. I built models and carefully airbrushed the camouflage and the insignias from each of the theaters of the war, so I had a dogfight from the Pacific War hanging in my bedroom in one corner and the African and European theater in another. I think that was part of it, most boys like the idea of war, too. I raced bicycles and motorcycles, so I also like the idea of a certain amount of risk. It seemed cool, so my thought was, go into the Air Force and become a pilot, and then become a commercial pilot and that would be my career. But I met a guy who was a pilot, he was a friend of the family, and I was telling him about my plan. And he was like, “Oh you don’t want to do that, my job is terrible.. blah blah blah…” I was about 14 or 15 and I was like, OK. Well that’s not going to work.

I learned a couple things there. Later I met him and I was like remember that time you told me… He said “No, why would I say that, I love my job! I work five days, and spend 15 days in Hawaii, and then I work another five more days.” I was like, “Ahhhhhhhh!” So what I learned was to be very careful when you give advice, because the person might take it. I tend to either tell that story or disclaim advice and suggest that you don’t take it, but you only use it as a little data point. Be careful about advice.

What do you love?

I love my kids and my wife and my family, but everybody loves those things. It’s changed over time; there have been times where I have really loved doing things that other people noticed. Recognition. Like when I was young I loved recognition. I think I still like it. But I really loved it, I worked hard and everything I did was to be recognized. And then something happens when you get a little bit older. For me now, I don’t do it all the time, but what I LOVE, is mentoring other people. Meeting people. Just sort of, pulling out of them, what it is that they want to do, and in a way, connecting them to it, make them realize what it is, make them realize they can achieve it. And then help them a little bit, too, connect them with other people and help them make that a reality.

What is something you had to learn the hard way?

I think it’s funny, because I know things and then I forget things. When you are creative, you have a kind of intelligence that is more of an emotional intelligence than IQ. Less analytical. I was very comfortable with that for a long time. The most significant decision I have made, I have made with, what I would call my gut.

So I would feel the decision, and then I would think about how I could support that feeling. Some people have the opposite process, where they have a feeling, then they try and see if their intellect can overcome that feeling. I did the reverse, I thought, “OK, I got this feeling, why is this feeling right?” Then I would support it. With my rational side.

There are times when I made much more rational decisions and although those, a lot people would think those were successful decisions, and most of them, if your measure is money, were successful decisions, but I always use happiness as the measurement. And if you used happiness to measure those decisions, they were not successful.

My father-in-law teaches Leadership, and he is a former Harvard professor, a Stanford professor. He has written about leadership and studied leadership. I was telling him about my process, and he asking about my decisions and I only made a few decisions that I feel that were a mistake, and those were decisions I made with my head instead of my heart.

He asked, “Tell me how they turned out?” I said, “From your point of view, I think you would consider them a success, because they made me a lot of money. But from my point of view, they led me the wrong direction and they made me less happy.” If that is the measurement, then I think I learned the hard way to continue to trust, to support my gut and my heart.

What is one thing most people would be surprised to learn about you?

Most people are surprised that I’m shorter than they thought. I’m 5’9”. (laughs) People are going to think I’m tiny now.

What personality trait is most important in success?

Set your definition before you get started, I already knew what I wanted it to be. I didn’t get it from somewhere else, the American Dream was out there. A lot of people defined it in different ways, and I just at some point said, what do I think it would be. I probably asked people, what do you like about what you do? I grew up around a lot of artists and stuff, I think it’s just a matter of, it shouldn’t be the same. That’s the worst thing about the American Dream. Is the Generican Dream. That it’s the same. How can that possibly be? That we all share the same dream? I think the original version of the American dream, was the promise- whatever dream you have, you can achieve it here.

We live in a pretty complicated time, politically, environmentally, socially…how do you think we can make the world a better place?

I guess I think about this a lot and it bothers me. I’m troubled by it personally. Sometimes I just lie in bed all day and I think that nothing I do matters. And other times I’m so excited, and feel that there is so much potential for anybody, including me, to make a difference.

The more time I’ve spent sort of looking at it and thinking about it, the only element is to believe you can, and then do something. You don’t need grand plans. You can wonder about it, you can critique it, but I wanted to communicate to people- just make sure you go. It’s amazing that just by standing up and saying, “OK. I’m just going to be here and witness this,” has its own power.

Maybe a lot of us have been convinced that we don’t have that much power. Is it school, is it life, is it culture? I don’t know. But it seems like a lot of people are left with the feeling that this situation is helpless and that situation is helpless. It’s too big for me. And a lot of the problems do seem enormous. And yet, when enough people, starting with one, say, “I’m going to do a little bit of something,” then time after time these seemingly insurmountable problems or obstacles or groups or governments, standing in the way, just buckle under the pressure.

Let’s talk about the Fearless Cottage, how did it come to be?

It’s all a work in progress, because of a lot of what has happened to me has happened by accident. Or at least partly by accident. It’s not like I had this grand plan that was the Fearless Cottage. What happened was, I wasn’t really happy doing what I was doing. I started to recognize that, started to work on some different version of it. One of the things I was not happy with was that I felt like there were a lot of issues and in my position, as the co-chairman of a major agency, I wasn’t really in the position to talk about these things. I had a lot of conflicts, little by little I had more and more. So I thought, I’d love to agitate this industry from within, so that it could move a little faster in the direction that I think it probably needs to go. And in the direction a lot of people I know would like to see it go. I could probably help if I was halfway removed. So I tried that through the holding company.

When I actually started saying some of the things I thought I wanted to say, it created problems. The connection was too tight. It still created a lot of problems for the agency, and all the people I loved that were working there, whose values are not the same as mine. So, then at that point it’s like OK, this is a little bit different than I had planned, but now I have to step completely out. In the meantime, I’ve moved into the cottage, and I’ve got a certain amount of stuff going on. Do I keep that going? Or do I let go of the people that came with me? What’s the plan?

I thought I’d like to keep it going, I’d like to keep working with people that wanted to stick with this. When I looked at my energy, and sort of the first steps of that path, I thought I was sort of moving from being a brand advocate, speaking on behalf of the brand, and potentially moving into this consumer advocacy stage- but not like a Ralph Nader point of view, more from the point of view of “what is the expectations for relationships between consumer and brand?” and do we as consumers, when we buy something do we expect in return as much as we should? I think we expect much less than we should, from the companies that we do business with.

Part of the reason why that matters now, is because business has inserted itself into democracy. The money from corporations has moved into our democracy, so unless we consume and vote almost in a sensitized way, we are not operating within the realities of the current system. I don’t think it’s a perfect system – I’d like to see the money move out, but since the money is there, if we are going to leverage our potential to vote for and buy a world that matches our values, we have to work both simultaneously. So a consumer/citizen is more powerful today than someone that plays just in the political realm. Or vice versa. And that’s what we want to spend time talking about.

ALEX BOGUSKY:

Twitter: @bogusky

Fearless Revolution: www.fearlessrevolution.com

Made Movement: www.mademovement.com

COMMON: www.common.is

If you liked this interview, stay connected by following our Facebook page.

Erika Christensen, Actor

You might know Erika Christensen from her role as Julia Braverman Graham on Parenthood, or any of the amazing other roles she’s done. Case in point: Swimfan, Traffic, The Perfect Score, and just when you think she can’t get any cooler, she lends her voice to the hysterical Robot Chicken.

You might know Erika Christensen from her role as Julia Braverman Graham on Parenthood, or any of the amazing other roles she’s done. Case in point: Swimfan, Traffic, The Perfect Score, and just when you think she can’t get any cooler, she lends her voice to the hysterical Robot Chicken.

All that aside, Erika is down to earth and naturally gorgeous. She was so unbelievably kind and gracious, and most of all, she was really interesting and willing to share her favorite things with us.

Inventory is a project designed to feature creative and inspiring people who have an interesting story to tell. This series gives the readers an inside and intimate look at the lives of the subjects, through everyday objects that hold importance and have meaning.

For those of you who follow Erika, you know she’s an avid cyclist. Using the word “avid” is probably an understatement. Her bike was the first thing she wanted photographed.

Erika comes from a family of artists. Her brother gave her this piece, and it proudly hangs in her impressive collection of unique and personal art.

Her mother is also quite the artist. This is some of her work.

Her favorite tote is this Rapha shoulder bag. It goes everywhere with her, and is perfect for cycling.

Erika has a no-plastic-bottles rule, so these gorgeous glass bottles are a mainstay.

She started collecting Super 8s, and her mother recently gave her a projector- so be on the lookout for a fun film project in the future.

Cold-brewed coffee is a must.

Her favorite pair of shoes are Soludos. She says she has every design and wears them every day. Cute, casual and comfortable- what more could you want?

She’s a coffee nut, and loves her mocha pots.

Her favorite sunglasses.

A gifted porcelain tea cup from her grandmother.

ERIKA CHRISTENSEN ON SOCIAL MEDIA:

Twitter: @ERIKAjaneC

Instagram: @erikachristensen

All images by Duane Fernandez.

If you liked this story, stay connected by following our Facebook page.